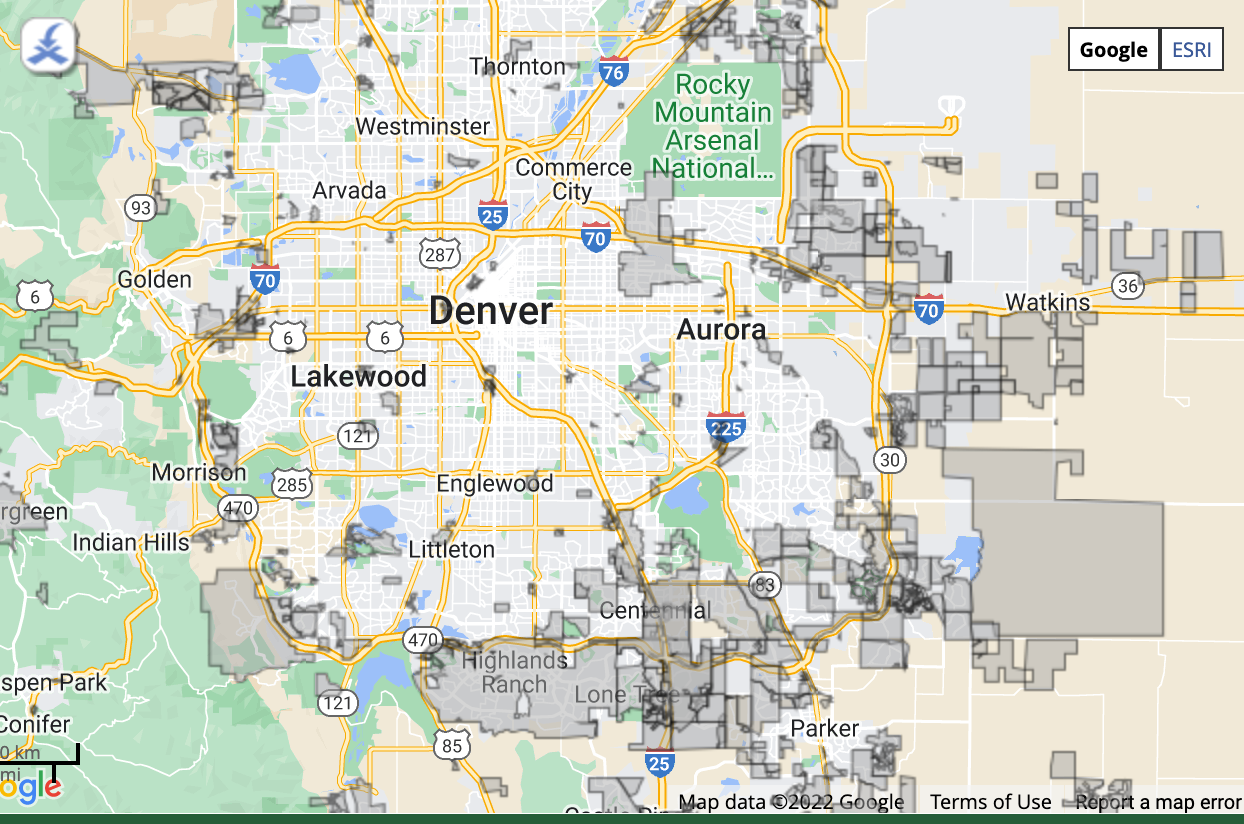

Metro Districts in Colorado

After four years of living in Colorado and trying out a few different areas, we recently got started on the process of buying a house. Since the real estate market is completely bananas, we thought it would make sense to look for something newly constructed — the builder tells you the price, and you either agree to it or don’t. No bidding wars, no competing cash offers that real humans can’t beat, no sketchy inspection waivers, no appraisal gaps to cover. Over the course of exploring new-construction neighborhoods, I heard about this thing called metro district taxes, which are property taxes levied over and above the city and county taxes. So what the fuck is a metro district, and how is this possibly legal?

Gathering information on this turned out to be a little tricky. The builder’s sales person couldn’t answer my questions, and gave me the contact info for someone at their district consulting company. A week after I emailed them, the contact eventually replied only to say “These are not typically questions that the District directly provides answers to,” and told me to ask the builder’s sales person. Grrrr. As a data nerd and information junkie, people who intentionally withhold knowledge piss me off.

But research is my superpower, so I discovered that most of what I wanted to know is public record and available online, you just have to dig for it. The most useful information I found was at the Colorado Department of Local Affairs, which is the state agency that regulates metro district activities. Their website has a handy list of tax entities you can view by county or alphabetically. Once you find the metro district in the list, you can read or download all of its documents. I recommend starting with Service Plans, Annual Budgets, and of course maps. I had to wade through a lot of legalese (watching this volunteer attorney‘s videos helped), but managed to answer most of my questions. Here’s what I learned.

What’s a metro district, and how is it formed?

Special districts are mini government entities that allow private land developers to recoup the costs of building modern infrastructure, such as roads, sewers, and powerlines, on undeveloped land. These entities follow an old English custom used for drainage and irrigation that dates back to the 16th century. Special districts have existed here in the US since the 1800s, but were not well documented until the 1940s. Beginning in the 1980s, builders in Colorado wanted to get in on the fun, and lobbied for their own version. As a result, the Colorado Title 32 Revised Statutes for Special Districts were born.

Now, when a Colorado builder wants to create a new neighborhood, they can petition the local city and/or county for permission to create a Title 32 Metropolitan District. If approved, this neighborhood becomes its own little part of the government, and is granted authority by the state of Colorado to levy taxes on its eventual residents. The money from these taxes is used to pay the debts (mostly in the form of tax-exempt municipal bonds) incurred for building the initial infrastructure, as well as fund ongoing costs during construction, maintenance and services after the community is complete, and potentially, nice bonuses for builders.

Are metro districts good things?

There are reportedly over 4,000 metro districts in Colorado, and whether they are good or bad depends on both perspective and how well they are managed. Creating metro districts allows the builder to charge less for the homes they are building, because otherwise they would have to roll all of those infrastructure costs into the home prices. This lower pricing makes the resulting homes more affordable for buyers, and easier for the builders to sell. However, it’s critical that prospective buyers are aware of metro district taxes and include them in their decision making process. These taxes can add thousands to a buyer’s annual tax bill, and therefore increase monthly mortgage payments (due to escrow) by hundreds of dollars. So the home buyer ends up paying for the infrastructure either way, but it’s more difficult for the buyer to predict their housing costs in a metro district because it’s not a fixed cost up front.

How are metro district taxes determined?

Like city and county taxes, metro district taxes are assessed as a percentage of home value (“assessment ratio”), and can therefore increase along with property values each year. However, unlike city or county taxes, metro district tax rates (“mill levy”) can change at any time without being voted on by referendum. If the community doesn’t get completed by the expected time, for example, fewer homes would have to bear the entire debt burden, and the district would raise the mill levy to cover it. These mill rate changes only have to be approved by the metro district Board of Directors, which is initially comprised 100% of people who work for (or are related to) the builder. In this situation, it can be considered a form of taxation without representation.

As a prospective home buyer, if you want to calculate your own metro district taxes, it can be a little cryptic. Builder sales people tend to quote the total tax rate as a percentage of the home value (such as 1% or 1.3%), but this includes the other local taxes as well. To calculate your own metro district taxes alone, you’ll need to get the local assessment ratio from the city and/or county website, and the metro district mill levy from its Service Plan. Here’s the formula:

Actual Value x Assessment Ratio x Mill Levy = Annual Tax Obligation

Example: For a $400,000 home in a Metro District with a 50 mill levy using the 2020 Assessment Ratio for residential property, the tax bill for the District would be:

$400,000 x 7.15% x 0.050 =$1,430/year

Source: Metro District Education Coalition

Are metro district taxes ever negotiable?

Nope. You buy a home in a metro district, you get a tax bill that includes the metro district portion. They are enforceable via tax lien, like any other property tax.

Is there a cap or limit on these taxes, or do they just increase indefinitely with the home’s value?

Some local jurisdictions do impose a cap, but the state of Colorado does not. The tax mill levy can be adjusted up or down, again, by board vote rather than voter referendum. Guidelines from the Coloradans for Metro District Reform recommend a maximum of 50 mills, with a preferred rate of under 35 mills.

Is there an end date?

Technically yes; realistically not so much. Because bonds are typically issued for 30 years, this is usually the limit, but it may be more. Our district of interest has a limit of “40 years from initial imposition,” but I am unclear whether this means the date the metro district first imposes any taxes, or the date each new home is purchased. If the district issues new bonds, say, to build new bike trails, that could restart the clock again. Yes, you get new bike trails out of the deal, but you have zero choice about whether to build them (and pay for them) or not. Ultimately, I don’t think this tax ever really goes away.

How do we know specifically what the money is being used for?

Per Title 32, a metropolitan district has to provide two or more types of improvements and services. Specific expenses for each metro district are found in its annual budget, which is public record. For our potential metro district, the list includes mosquito control, parks and recreation, traffic and safety control, sanitation services (sewer I think), street improvements, TV relay and translator, transportation, water, and operations and maintenance (landscaping, clubhouse, pool, etc.). That’s about as detailed as it gets, but it’s a start.

What’s the difference between a metro district and an HOA?

A metro district is a mini government entity that can levy taxes to fund community expenses. An HOA is a private neighborhood organization that can also charge fees for similar things, but it’s not part of the government, and their dues are not taxes. Some neighborhoods combine everything into the metro district taxes and claim that it’s better than paying HOA dues because taxes can be written off (more on that below). Some communities have both metro district taxes and HOA dues or maintenance fees. If you are considering buying a new home in Colorado, it’s worth asking very specific questions about whether one or both apply, and if so, what the fees are and what is covered by those fees.

Do metro district taxes apply only to new construction?

Nope. Existing homes may fall into a metro district, especially if they are newer.

Since these are property taxes, can they be written off?

TBD. Builders and real estate sales people claim that they are deductible in some cases. I was told by a mortgage loan officer that they usually are not.

Who is the metro district accountable to?

Primarily, only itself. The developer issues the debt, taxes the residents to pay the debt, and decides how much profit to pay itself. From our proposed metro district again:

“All of the members of the Board of Directors during 2020 were employees of, or consultants to, [parent company name], a Colorado corporation doing business as [builder name] and the major landowner, developer, and homebuilder of the property within the Districts.”

However, as soon as a resident buys a property, they can serve on the Board and widen its scope of accountability. More on that below.

Can the metro district system be abused?

Absolutely, especially if nobody is paying attention. There do appear to be legal loopholes that benefit builders. I heard anecdotally about one builder who used his metro district to assure passive income for his heirs for the next 30 years. However, it’s worth checking your local city and county government websites. Some areas will pretty much rubber-stamp metro districts, and approve everything the builder wants to do. But some cities in Colorado, including Aurora, Longmont and Westminster, have adopted additional policies, limitations, and guidelines around metro districts. Cities are not required to approve metro districts’ proposed terms, and can create conditions to help make sure they are being used as intended.

How can the potential for metro district abuse be reduced?

Get involved locally. The most direct way to have an impact on your metro district is to nominate yourself to its Board of Directors, which you can do as soon as you buy a home, and encourage your neighbors to do the same. New directors are elected by the community annually and serve 2-4 year terms. Adding more homeowners to the Board can take some time, if you have to wait out each Director’s term and deal with frequently-cancelled elections. In the meantime, if the developer has 7 votes and homeowners only have 1 or 2, residents will get outvoted every time.

Like working on your HOA board, serving as a metro district Director can be a thankless and time-consuming job. But if enough committed homeowners join the board, it can become homeowner-managed and actually represent the needs of the community rather than the builder. Here’s an example of a mature, transparent homeowner-managed metro district that incorporates 14 different builders and an HOA: Fronterra Village